The Beauty That Will Not Save the World in Contemporary Russian Art • Hyperallergic, May 2016

MOSCOW — If you were to go only by the types of exhibitions you see in Moscow galleries — and there are very few of them — you would get only a partial view of what’s happening in art in Russia. This would be true anywhere, but it’s particularly telling in a major world capital that has managed to remain constantly isolated from international critical and curatorial practices, intersecting them only aleatorily. This isn’t a question of being at the “margins” of the art world — a term often used to refer to artistic practices from the postcolonial world — but rather of being a different kind of center, one that remains turned inward, toward itself. The unique characteristics of Russian contemporary art cannot be briefly summarized, but it sits at the intersection of the bizarre legacy of Socialist Realism, the wide-ranging influence of the Moscow Conceptualists, and the constant referencing of 20th-century avant-garde. In the strange world of Soviet pop art, rife with the precariousness of visual language and sophisticated humor, a lot of the art remains impenetrable to the touristic curator without serious research. The galleries, therefore, can offer only so much in the absence of a real market, and the offerings are limited to a tiny batch of names for a country of this size.

But that’s not the whole picture. The lack of institutional structure in Moscow is not a lack of institutions (there’s a network of municipal exhibition halls and central state institutions) but a lack of institutionality — transparent, accountable institutions, grants, residencies, and so on. The way Russians artists have responded to this condition historically is via an underground of informal discourse and exhibition. Since Soviet times, artists have been cementing networks of communication by showing their works to each other and discussing them, later making exhibitions in apartments, studios, and workshops. And this informal art world is still very much alive. Of course, you can tell these are not the wild 1990s when everything was possible, and, as you can see in the book Reconstruction published by Garage Museum about the period, or Collection of Ekaterina and Vladimir Semenikhin. Selected Works 2000–2005, the current exhibition at Ekaterina Foundation, most of the galleries and spaces from that period no longer exist. The disappearance of Russian galleries and artists from the global art circuit, due to the geopolitical isolation of Russia, the financial crisis, and economic sanctions, makes it all the more important to look at the informal art scene as a whole, in order to get a sense of what’s going on.

Recently Iragui Gallery, a small space with strong international presence, invited Alexander Zhuravlev, a young curator who has experience with municipal exhibition halls, to put together an exhibition. The result was Raw Magic, a group show featuring work from truly emerging Russian artists. These are not the professional “emerging” artist of the art world, but actually really young artists, and for many of them it was their first appearance in a white-cube gallery. This type of exhibition is unusual in Russia, but Iragui had gone down this road before, handing over the space from time to time young curators so they can realize projects with little market impact. Raw Magic was centered on the return to surrealism not only as a style but as the juxtaposition between different realities. And we do live in such a world: lost in the endless stream of the internet, the mass media loop, the spectacle of consumerism, and our fragmented selves, unable to reclaim a safe, definite place in one reality or another. Since the concept of reality is no longer obvious, or a mere structure that needs to be demolished as in 20th-century Dada, but mutually constructed by networks of social phenomena, communities, and their interactions, Zhuravlev conceives of reality as an interface of dialogues.

Artists in Raw Magic were invited to argue a viewpoint on reality through their work, and to conjure a dialogue about the possibilities of communication in a fragmentary world. The results were far from smooth, consistent, or even necessarily satisfying, but they demonstrated the difficulty of the task at hand: How do artists communicate in a situation in which there are no meeting grounds and the unconscious is identical with alienation? Relational networks emerged between the works, born out of the conceptualist preoccupation with the function rather than the form of art. Dima Kavko and Protey Temen stood out since they are both designers who turned to art in the search for a more holistic view of the object, producing works that seem finished in form while still retaining a lot of the fluidity of street culture. Kavko’s sculptures, titled after animals, are made from cheap everyday materials and constituted the most surrealistic works in the show, though they are also tinged with a post-internet flavor. Temen’s large black-and-white drawing “Cosmopolitan” (2016), on the other hand, was almost the centerpiece of the exhibition, inviting the viewer to a near-dream world where strange things happen.

Then there were the Kabbalistic drawings of Mitya Zilberstein and his found objects that helped make sense of his narrative — he is fundamentally a graphic storyteller — next to the watercolors of Matvey Segal, full of anthropomorphisms and historical characters, overlapping in time and very skillfully executed. These works were the only ones in the show that touched on both surrealistic aesthetics and magic. In a third group, there were works by Alina Glazoun and Alexey Rumin, which only indirectly referred to surrealism or magic, instead addressing questions of language and communicability that Zhuravlev wanted to raise. Glazoun’s pseudo-architectural boxes are whimsical and somewhat illogical urban forms inspired by songs titles, and Rumin’s miniature installation “Souvenir Shop” (2014) is made of 45 tiny 3D-printed objects that each inspired by a line in a book, from Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea (the piece is aptly called “Intestine Neck,” 2016) to lectures by prominent Russian curator Viktor Misiano, to Rem Koolhaas’ Delirious New York. All of these works interrogated how art is positioned in relation to the cultural languages we speak today.

The rest of the works in the show were perhaps not exactly in conversation, and their inclusion made the whole thing feel less like a concept and more like curatorial circle. Yet Zhuravlev’s central idea remains poignant in addressing the possibilities of a borderless kind of communication beyond aesthetic codes, formalistic approaches, and theoretical underpinnings. Raw Magic took its cue from the breakdown in reality that is daily life in Russia’s lingering state of chaos, aiming to transform the possibilities afforded by this void into new mental structures through which we can hear a plurality of experiences. Zhuravlev told Hyperallergic: “The idea that beauty will eventually save the world still haunts the minds of Russian people, though many artists do not acknowledge it. But later it became a taboo, after conceptualism evolved and they tied in aesthetics and ideology, seeing beauty as a propaganda tool. Nowadays, young Russian artists are so successful in avoiding anything beautiful that they actually rarely do anything, and it’s difficult to ignore the lack of communication between them. This exhibition addresses the problem of social and artistic difference, and turns to surrealism for its ability to put a viewer in a psychological state of accepting different realities at once, which is necessary for dialogue.”

But the informal art scene in Moscow takes on forms other than the gallery walls. The collective space Red Center, run by artist Irina Petrakova and curator Boris Kliushnikov in the Red October area, often presents exhibitions of this kind, such as the one-night-only exhibit in February, where a number of artists showed and explained their work to curators and other artists; it was there that I discovered the wonderful paintings of Vitaly Barabanov, whose performative works involve walks in the city and the preparation of food, with the material on the canvas only a residual practice. Red Center is very active with experimental exhibitions; on May 18, the center opened Near Far, showcasing works by Igor Astapchenko and Sergei Riapolov and curated by Ivan Novikov, which deals with the complicated relationship between urban and rural in our times, and the understanding of nature as a political process in the Anthropocene. In the absence of professional art magazines for this scene, there are active blogs and communities on Facebook that write piquant reviews and stimulate lively discussions about artists and their works.

The director of the Austrian Cultural Forum, Simon Mraz, a longtime diplomat in the country and a known personality in the Russian art world, hosts regular high-quality exhibitions in his apartment in central Moscow that can be visited by appointment. Recently, Mraz hosted the group show A Rose Has No Teeth, curated by Andrey Parshikov, who works at Manege, one of Moscow’s leading municipal art institutions. The exhibition addressed the reality of censorship and the many legal restrictions in place for artists in the Russian context, also tackling the queer narrative, which would have been difficult to get away with in an institution, both in terms of content and context. Parshikov included works such as “White Male Art” (2016) by Alexander Obrazumov, raising the issue of queerness in the white-male-dominated art of the 20th century, or Antonina Baever’s “Transatlancyxa” (2016), a neon sign with a play on the word “trans-Atlantic” and the slang for “fag” in Russian; the piece connected the current fluctuation of migration and national borders with the nature of queer commentary. According to Parshikov’s exhibition text, Obrazumov and Baever “work with the reality of the digital dualism, with the text, with certain cultural codes of communities.”

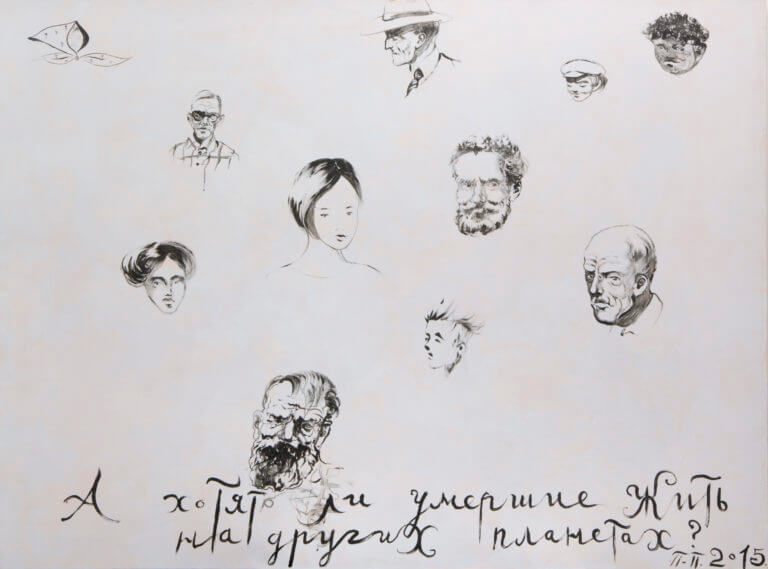

Another informal and particularly interesting show in Moscow is The Alternative Theories of Evolution, hosted at the Darwin State Museum, a natural history museum, put together by another young curator, Vlada Trubacheva. Why take a contemporary art exhibition to a natural history museum? Upon entering the building, surrounded by science exhibits, taxidermy, and the Soviet space program — all of them particularly outdated — the reason becomes clear immediately. The show is hosted in a tower at the top of the building with a ribonucleic-like shape. The theories of evolution are not only the history of human aspirations, but they also hold a special place in Russian art, with the profound influence of Cosmism and science fiction in literature, plus the art and politics of the Soviet Union, now being rediscovered by cultural practitioners. This exhibition is far from seamless, and at times the concept might seem vague, but there is almost magic being conjured by the different narratives, from aspiring artists who are being shown for the first time to very established names like Pavel Pepperstein, one of the major Russian painters of this generation.

Pepperstein’s work tells a fascinating story about Cosmism and the early Soviet science fiction. The diversity and scope of the exhibition can be confusing, but it also comes across as refreshing and surprising. Three artists present in Zhuravlev’s show are here again: Temen, Zilberstein, and Segal. However, the generosity of the space presents them in a more comprehensive fashion, letting their works breathe and speak a clearer language. There are some true gems in the show, such as the painting “Air Architecture” (2015) by Ilya Kisselman and two Anthropocene-themed works by Arcady Nasonov, “Life Without People” (2016), where the world (and data) have been taken over by underwater creatures. One of show’s central works is a painting by young architect Rinat Mustafin, “Formula of Evolution” (2016), which is literally a painted mathematical formula that Mustafin saw in a Soviet-era film and which he is still trying to figure out the meaning of. Throughout this show, theories of evolution become a gate to surrealism, fantasy, suprematism, and the fabrication of history.

A complex narrative installation by Russian Israeli artist Sophia Israel, “Doctor’s Plot or the Research Institute of the Brain” (2013), includes a model of the institute, and different models of narration — sculpture, script, painting, cartoons — that tell the story of a famous episode in Stalin’s regime, when the institute was founded for the study of Lenin’s brain. The story becomes even more complex when the viewer learns that Israel’s grandfather worked at the institute: she is telling a story, however fictional, from its very source, playing on the notion of history versus science. In the course of the exhibition, the science behind evolution dissolves and opens up channels that sometimes seem occultist and theological, sometimes political and propagandistic, and sometimes ironic. Trubacheva’s exhibition is not entirely distant from Zhuravlev when confronting different versions of truth and reality, so the shows become complementary and share similar preoccupations with the nature of alienation in contemporary Russia and the role of science fiction, which is central to Pepperstein’s work.

Looking at these shows and initiatives might lead us to romanticize the pervasive sense of informality in contemporary Russian art, but it is also necessary to remain critical and realize that at times the curatorial concepts seem so theoretical that they reduce the works shown to a network of functional relations in which art becomes secondary, while at the same time the curators haven’t had enough time to pursue intensive research in their artistic selection — they worked with what was available. This doesn’t necessarily have to be a weakness; it can be understood as a process of experimentation in a scene that is very young and dynamic, which bears of a history of its own. At the same time, this informality is also a symptom of a widespread lack of support for art in Moscow, meaning that however interesting these works are, it is uncertain whether the efforts will help consolidate artistic practices or will remain isolated efforts. Despite all this, there is a coordinated effort to recover reality from the fantasies of neoliberalism and authoritarianism, thus rehabilitating the public domain for a possible future dialogue.